Day 1: Tuesday, January 10, 2017 - Text Adventures¶

Table of Contents

Our short and brutal journey in computation¶

I have a few thoughts on the unique difficulties inherent in mixing journalism and computation.

But Tufte’s tweet sums up my mindset:

When they say it's about the journey, you can be certain that you're not going to get very far.

— Edward Tufte (@EdwardTufte) March 24, 2016

Our “journeys” will be short, at least the technical concepts. The level of programming is short and sweet, and “brute force” is good enough, because the bottleneck in getting thigns done is not a technical one. When this class becomes frustrating, it’s because the work of journalism constantly runs itself into the hard problems of computer science.

What is a computer?¶

I’ve liked using Paul Ford’s dissertation, “What is Code?” to explain the role of programming. The 38,000 word essay is a lot of fun to get through. But its best insight is near the top:

You, using a pen and paper, can do anything a computer can; you just can’t do those things billions of times per second. And those billions of tiny operations add up. They can cause a phone to boop, elevate an elevator, or redirect a missile. That raw speed makes it possible to pull off not one but multiple sleights of hand, card tricks on top of card tricks. Take a bunch of pulses of light reflected from an optical disc, apply some math to unsqueeze them, and copy the resulting pile of expanded impulses into some memory cells—then read from those cells to paint light on the screen. Millions of pulses, 60 times a second. That’s how you make the rubes believe they’re watching a movie.

But now I think that Ford isn’t reductive enough, that his description still makes a computer sound more elaborate than it is.

The fundamental building block of a computer is the bit. And no matter how many bits that computer contains, each of those bits is just something that is either on or off.

In his book, “But How Do it Know?”, J. Clark Scott explains how the simple bit becomes significant in our world:

A computer bit is still, and will always be, nothing more than a place where there is or is not electricity, but when we, as a society of human beings, use a bit for a certain purpose, we give meaning to the bit.

When we connect a bit to a red light and hang it over an intersection, and make people study driver’s handbooks before giving them driver’s licenses, we have given meaning to that bit. Red means ‘stop,’ not because the bit is capable of doing anything to a vehicle traveling on the road, but because we as people agree that red means stop, and we, seeing that bit on, will stop our car in order to avoid being hit by a car traveling on the cross street, and we hope that everyone else will do the same so that we may be assured that no one will hit us when it is our turn to cross the intersection.

So there are many things that can be done with a bit. It can indicate true or false, go or stop. A single yes or no can be a major thing, as in the answer to “Will you marry me?” or an everyday matter such as “Would you like fries with that?”

Scott, J Clark (2009-07-04). But How Do It Know? - The Basic Principles of Computers for Everyone (Kindle Locations 524-527). John C Scott. Kindle Edition.

What is a story?¶

- What makes a story “important”?

- How does a reporter know what is true and worth pursuing?

- How do award-winning journalists find their stories?

What are algorithms?¶

Stanford admissions

Text is our universal interface¶

Thinking of everything as plaintext will seem like a dumbing-down of computational methods. But only if you forget how all the code we write is in plaintext. And so is the vast majority of the data we will ever collect and attempt to understand.

Sticking with text is not a decision made out of nostalgia for a simpler time, but in recognition of the increasing complexity and speed of information.

As Graydon Hoare writes, in his essay Always Bet on Text

I like me some illustrations, photos, movies and music.

But text wins by a mile. Text is everything. My thoughts on this are quite absolute: text is the most powerful, useful, effective communication technology ever, period.

Text is the oldest and most stable communication technology (assuming we treat speech/signing as natural phenomenon – there are no human societies without it – whereas textual capability has to be transmitted, taught, acquired) and it’s incredibly durable. We can read texts from five thousand years ago, almost the moment they started being produced. It’s (literally) “rock solid” – you can readily inscribe it in granite that will likely outlast the human species.

...Text can convey ideas with a precisely controlled level of ambiguity and precision, implied context and elaborated content, unmatched by anything else. It is not a coincidence that all of literature and poetry, history and philosophy, mathematics, logic, programming and engineering rely on textual encodings for their ideas.

...So this is my stance on text: always pick text first. As my old boss might have said: always bet on text. If you can use text for something, use it. It will very seldom let you down.

The joy of text¶

In subsequent lessons, we’ll see how powerful text can be. Working with plaintext data has been the core of even the most complicated data investigations. And when we work with objects that can’t be represented as just plaintext, we still use text to describe those binary blobs.

Webpages, of course, have long been able to incorporate multimedia because text is used to describe the address, the format, and the appearance of multimedia assets. This universally beloved YouTube experience, for example, is encapsulated with this short text snippet:

<iframe width="853" height="480" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/dQw4w9WgXcQ?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen>

</iframe>

The Spotify API uses a bevy of structured plaintext objects to represent its vast music and artist collection.

With a human-readable label and a bit of URL-safe encoding, e.g. “Palace+of+Versailles+France”, Google’s Maps Street View API delivers us a plaintext Internet address <https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/streetview/intro>:

https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/streetview?size=600x300&location=Palace+of+Versailles+France

And that URL resolves to this image:

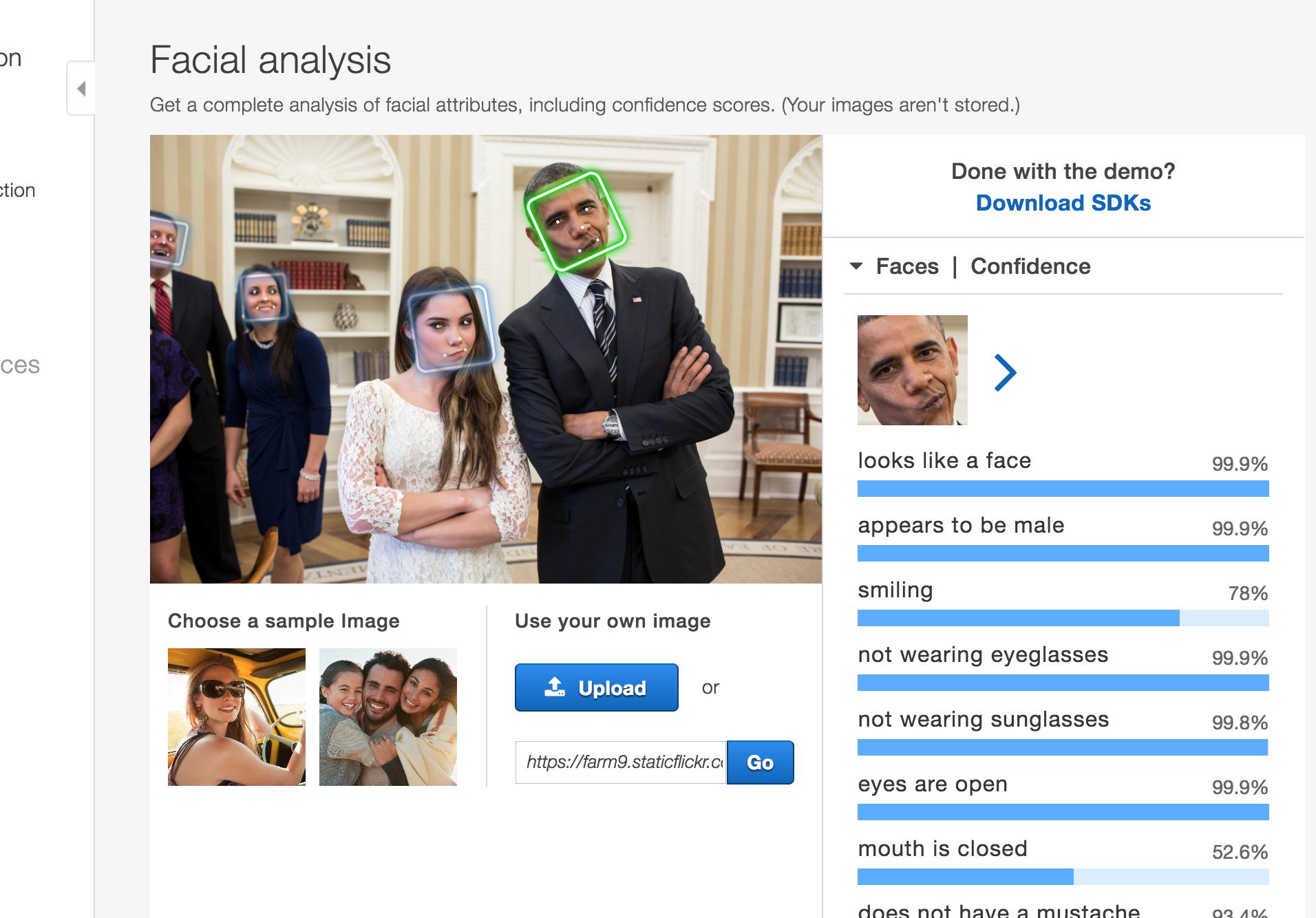

Even as we won’t have the time to cover the interesting theory behind methods like computer vision, we have plenty of ways to access and leverage that functionality. Amazon’s new Rekognition API doesn’t just detect faces, but returns a huge JSON data object that we can handle in our programs just like any other text string:

https://console.aws.amazon.com/rekognition/home?region=us-east-1#/face-detection

Test image via Flickr/White House

On Thursday, we dive into the OS X command line. Even in an all-text interface, we have easy ways of making audio.

$ say what

Lab practicum¶

- Log on to the lab computers

- Regular expressions

- The Atom Text Editor

For next class¶

Readings¶

Here’s a small collection of articles, both past and present, about fake news and other hoaxes:

An overview of current and historical fake news

Pick a couple articles to read, just to get a better sense of the controversy. I personally like these two:

Install Atom Text Editor¶

Note

It’s OK

The following section talks about installing software. Try to get it done if you can, because that gives me extra lead time to help you if there is an issue. There’s no deadline (yet). I’m purposefully staggering the pace at which we install or try out things, rather than wait till when we need them to get a bad surprise.

In the next few weeks, we’ll be doing more work from our own computers rather than the McClatchy Lab. The Atom text editor is not only free but well-supported and popular among developers. As we write more complex scripts, you’ll want to be doing this from your own computer.

So try to install the Atom text editor on your own machine by Thursday, so you can begin writing scripts on your own.

Atom.io - A hackable text editor for the 21st century

Note

Using Atom is not mandatory. I assume if you’re using a different editor, like Visual Studio Code <https://code.visualstudio.com/> or Sublime Text (my favorite), that you know what you’re doing.

Install Google Chrome and Secure Shell¶

Browser development tools are critical to understanding web-development and web-scraping. Chrome has great tools, and more importantly, I know them well and can provide consistent advice.

If you haven’t already, you can download Chrome here: https://www.google.com/chrome/browser/desktop/

However, you don’t have to make Chrome your main browser. In fact, there’s no reason why you should let another browser/company hold on to your credentials.

Installing a new user profile on Chrome¶

What if you already use Chrome as your default browser? Then follow these instructions to create a new user profile: Chrome Help: Add a new user profile

For all intents and purposes, it’s like adding a new user to your computer in that their settings, passwords, plugins, etc. won’t affect your Chrome profile. Having a separate profile reduces the risk, for example, that you run Twitter bot code from this class on your “real” profile. It also helps with web development, so that plugins from your personal account, such as ad blockers, don’t interfere with this new account.

Get a glaring new theme¶

You can run multiple Chrome windows at the same time for multiple users. It’s very easy to get confused, so I recommend going to the Chrome themes store and picking a color scheme that is obviously different from your normal one.

Install the Secure Shell plugin¶

This step is mostly for Windows users who don’t have a great way to connect to remote computers in the way that OS X users have Terminal. It’s entirely optional, but if you’re on Windows, you might find it easier to use than the usual Windows SSH client.

The Secure Shell plugin can be downloaded from the Chrome store