Solid Serialization of: Trump Tweets as JSON from Twitter API¶

Contents

- Solid Serialization of: Trump Tweets as JSON from Twitter API

- But Why???

- Deliverables

- Prompts

- 1. Count number of tweets

- 2. Count number of original tweets

- 3. Count number of retweets, quoted tweets, and regular tweets

- 4. Calculate total number of times retweeted, and average retweets per tweet

- 5. Get the id, created_at, retweet_count, text of the 5 most retweeted tweets

- 6. Do a group count of tweets by yearmonth

- 7. Do a group count of tweets by hour, adjusted for Eastern time

- 8. Count of tweets by device

- 9. Tweets by hour using an Android phone

- 10. Number of tweets that use the word “crooked”, Android vs. iPhone

This assignment is part of: Solid Serialization Skills

In the previous assignment, we dealt with Trump tweets, except in a simplified CSV format:

Solid Serialization of: Just Trump Tweets (CSV)

Now, we’re going to use the actual JSON-formatted data that using the Twitter API will deliver. But we’ll just pretend we’re using the API when we’re actually using just a saved response from the API:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/realdonaldtrump-tweets.json

In the end, it’s the same concept of deserializing a particular kind of data-as-text into Python data objects and looping through and filtering, except just dealing with all the noise of complexity of Twitter’s data.

But Why???¶

Now, we’re going to use the actual JSON-formatted data that using the Twitter API will deliver. But we’ll just pretend we’re using the API when we’re actually using just a saved response from the API:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/realdonaldtrump-tweets.json

In the end, it’s the same concept of deserializing a particular kind of data-as-text into Python data objects and looping through and filtering, except just dealing with all the noise of complexity of Twitter’s data.

For this assignment, the complexity of Twitter will be a curse. But when you want to do something interesting with the data, you’ll appreciate the granularity that Twitter provides, and you’ll see how the Twitter API is used to fuel such projects as:

- Text analysis of Trump’s tweets confirms he writes only the (angrier) Android half http://varianceexplained.org/r/trump-tweets/

- Here’s What Happens When @realDonaldTrump Tweets A Link https://www.buzzfeed.com/alexkantrowitz/heres-how-much-traffic-a-trump-tweet-drives?utm_term=.swW6LY6wm#.dvXAJ7A9v

- Creator of @everyword explains the life and death of a Twitter experiment https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2014/jun/04/everyword-twitter-ends-adam-parrish-english-language

- How to make a Twitter bot: http://tinysubversions.com/2013/09/how-to-make-a-twitter-bot/

- Politwoops: Explore the Tweets They Didn’t Want You to See https://projects.propublica.org/politwoops/

- An algorithm to figure out your gender: http://boingboing.net/2014/09/01/twitter-uses-an-algorithm-to-f.html

- The 307 People, Places and Things Donald Trump Has Insulted on Twitter: A Complete List https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/01/28/upshot/donald-trump-twitter-insults.html

- @nytminuscontext https://twitter.com/nytminuscontext

- Everyone has Fake Twitter Followers, But Trump Has The Most. Sad! https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/everyone-has-fake-twitter-followers-but-trump-has-the-most-sad/

- When Trump Attacks! https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/when-donald-trump-attacks-gop/

- Twitter bot or real, live person? Site picks out fakes instantly http://www.welivesecurity.com/2014/05/07/twitter-bot-real-live-person-site-picks-fakes-instantly/

Deliverables¶

You are expected to deliver a script named: trump_tweets_json.py

The data file to use is:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/realdonaldtrump-tweets.json

This script has 10 prompts, which means at the very least, your script will contain 8 separate function definitions, from foo_1 to foo_10.

When I run your script from the command line, I expect to see something like this:

$ python trump_tweets_json.py

Done running assertions!

And I expect your script to have this code at the bottom:

def foo_assertions():

assert type(foo_1()) == int

assert foo_1() == 3225

assert type(foo_2()) == int

assert foo_2() == 3048

assert type(foo_3()) == dict

# this number varies depending on how much you care about

# twitter minutiae

assert abs(foo_3()['plain'] - 2982) < 5

assert type(foo_4()) == dict

assert foo_4()['total_retweet_count'] == 28343617

assert type(foo_5()) == list

assert len(foo_5()) == 6

assert foo_5()[0] == ('id', 'created_at', 'retweet_count', 'text')

assert foo_5()[1][2] == 348986

assert type(foo_6()) == list

assert foo_6()[5] == ('2016-06', 303)

assert type(foo_7()) == list

assert foo_7()[-1] == ('23', 153)

assert type(foo_8()) == list

assert foo_8()[1][0] == 'Twitter for iPhone'

assert type(foo_9()) == list

assert foo_9()[5] == ('04', 60)

assert foo_10() == {'crooked_android_pct': 12.1, 'crooked_iphone_pct': 5.4}

if __name__ == '__main__':

foo_assertions()

print("Done running assertions!")

Go simple first¶

The data file is pretty massive:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/realdonaldtrump-tweets.json

And just in case you want to compare, here is Hillary Clinton’s tweets (this is optional):

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/hillaryclinton-tweets.json

So the first thing you should do is write a method for downloading, caching, saving a file so you only write it once.

But even before that, you should get comfortable with all that a tweet can entail.

Twitter’s documentation is an OK place to start, especially if you already know how Twitter works: https://dev.twitter.com/rest/reference/get/statuses/user_timeline

But if you don’t, you need to be aware of a few things about each tweet data object. Or at least explore them as such:

Here’s a file that represents a single simple tweet:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/simple-tweet.json

Here’s the live tweet, a rather old one:

https://twitter.com/jack/status/20

Here’s a more complicated tweet, one with many nested serializations, including multimedia objects and hashtags:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/complex-tweet.json

Here’s what it looks like on the web:

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/756171983407243264

And then there are other kinds of tweets, such as a “retweet”, which is important for this lesson, and adds yet one more thing to programmatically explore:

http://stash.compciv.org/2017/retweet.json

https://twitter.com/IvankaTrump/status/815413345935355904

In the interactive prompt, download each individual JSON and try to explore each tweet individually, after deserializing it. Given a tweet object, how do you find when it was tweeted? How do you get the timestamp? The number of retweets? Whether it was itself a retweet?

Then, to do these exercises, you apply that same methodology on a list of tweets. But better to start off with a simple tweet and work out to bigger collections.

Prompts¶

1. Count number of tweets¶

A collection (i.e. a list) of tweets deserialized from JSON is the same as it is from CSV. Return the length of the collection of tweets from the downloaded and parsed data file.

Expected results:

3225

2. Count number of original tweets¶

So every tweet associated with @realdonaldtrump is initiated by whoever controls that account. But some tweets are retweets, that is, the user is just literally passing along someone else’s tweet along verbatim.

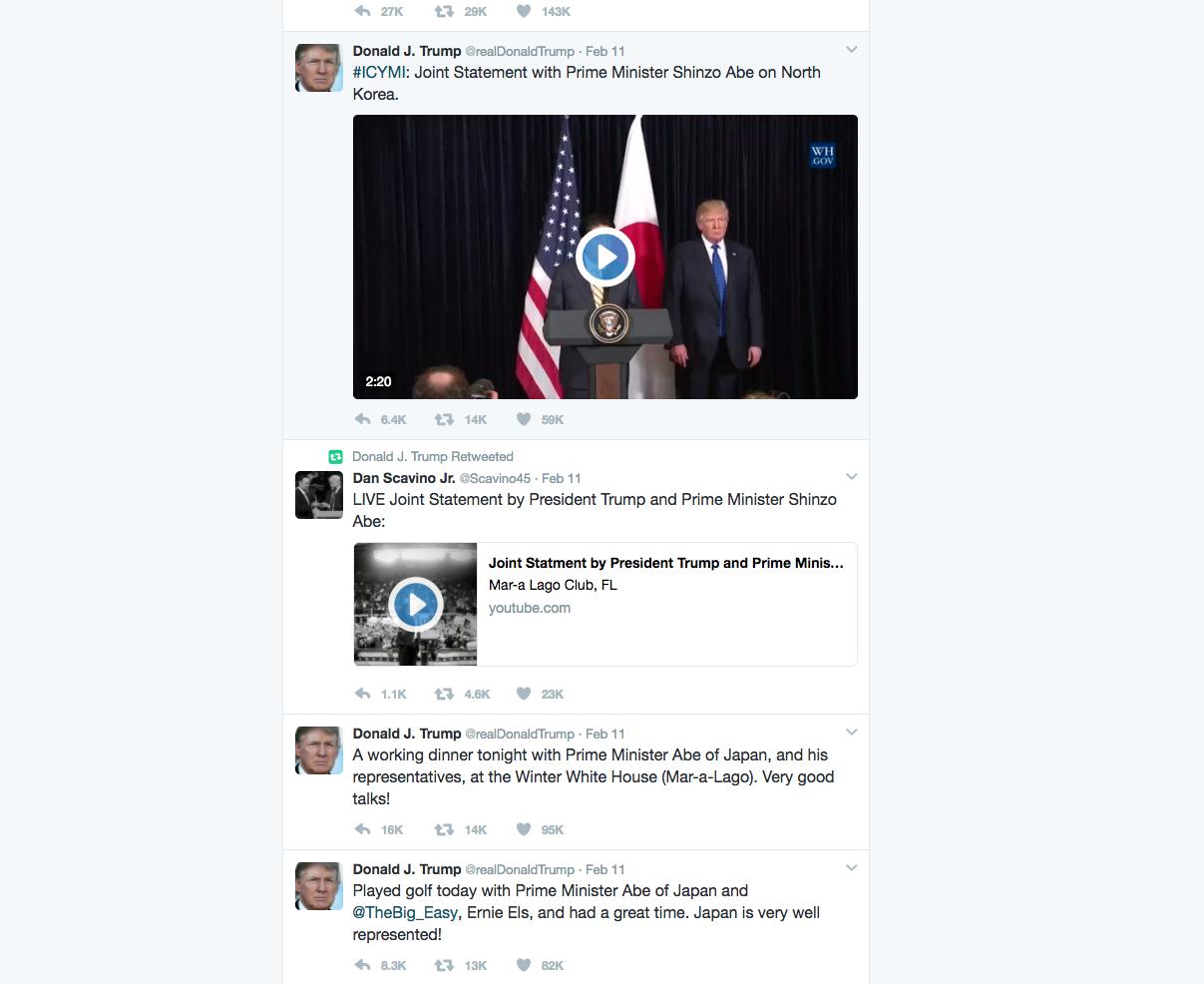

Below is a screenshot of @realdonaldtrump’s timeline, which features a retweet from the user with a screen name of @Scavino45:

Return the count of tweets that are not retweets as an integer:

Expected results:

3048

3. Count number of retweets, quoted tweets, and regular tweets¶

Return a dictionary that groups the tweets by type – quoted tweets, retweets, and everything else (plain) – and has a group count for each type of tweet.

Expected results:

{'plain': 2982, 'quoted_tweet': 66, 'retweet': 177}

Note

Data warning

You may not get the same count as I do depending on how you filter for what a “quoted” tweet is. There are multiple ways in the tweet data object, including checking for the keys quoted_status or is_quote_status.

The difference is in how you interpret a tweet like this:

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/815432169464197121

The above tweet is a retweet by the @realDonaldTrump account of this tweet by @DanScavino, which is itself a quoted tweet:

https://twitter.com/DanScavino/status/815425454807072768

In its data object, the quoted_status key/value is non-existent, while its retweeted_status does exist, as is what we expect for a retweet. But is_quote_status is set to True...go figure.

Hints¶

A “quoted tweet” is a tweet like this, in which the user retweets someone but adds their own commentary.

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/793802617428160513

A “retweet” is a tweet like this, in which the tweet is exactly the original tweet (note that the URL below redirects to the original tweet that is being retweeted):

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/815449933453127681

You should be doing this in the interactive shell to figure out how this is signified in the tweet object – find the tweet object with the id that I’ve specified above, and examine its structure:

>>> example_quoted_tweet = next(t for t in trumptweets if t['id'] == 793802617428160513)

Note that the above is the “Pythonic”/fancy way of doing a for loop until you find the first tweet that passes the given conditional expression:

example_quoted_tweet = None

for t in trumptweets:

if t['id'] == 793802617428160513:

example_quoted_tweet = t

break

4. Calculate total number of times retweeted, and average retweets per tweet¶

Each tweet object as a 'retweet_count' key. Filter all the tweets for non-retweets, then sum up the ‘retweet_count’, and use that to calculate an average.

Return a dictionary:

Expected results:

{'average_retweet_count': 9299, 'total_retweet_count': 28343617}

5. Get the id, created_at, retweet_count, text of the 5 most retweeted tweets¶

Sort non-retweets in descending order of retweet_count. Then return a list of the id, created_at, retweet_count, and text of the 5 top tweets as a list of tuples.

Expected results

[('id', 'created_at', 'retweet_count', 'text'),

(795954831718498305,

'Tue Nov 08 11:43:14 +0000 2016',

348986,

'TODAY WE MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!'),

(796315640307060738,

'Wed Nov 09 11:36:58 +0000 2016',

224084,

'Such a beautiful and important evening! The forgotten man and woman will never be forgotten again. We will all come together as never before'),

(741007091947556864,

'Thu Jun 09 20:40:32 +0000 2016',

167284,

'How long did it take your staff of 823 people to think that up--and where are your 33,000 emails that you deleted? https://t.co/gECLNtQizQ'),

(815185071317676033,

'Sat Dec 31 13:17:21 +0000 2016',

130715,

"Happy New Year to all, including to my many enemies and those who have fought me and lost so badly they just don't know what to do. Love!"),

(755788382618390529,

'Wed Jul 20 15:36:06 +0000 2016',

119732,

"The media is spending more time doing a forensic analysis of Melania's speech than the FBI spent on Hillary's emails.")]

6. Do a group count of tweets by yearmonth¶

Make a list of tuples, with each tuple containing the month as a string ("2017-01") and the count of tweets that month as an integer, e.g. 6

The list should have a header tuple of ('month', 'count'), and it should be sorted in ascending order of the month string.

Expected results:

[('month', 'count'),

('2016-02', 44),

('2016-03', 441),

('2016-04', 283),

('2016-05', 350),

('2016-06', 303),

('2016-07', 358),

('2016-08', 283),

('2016-09', 296),

('2016-10', 531),

('2016-11', 193),

('2016-12', 137),

('2017-01', 6)]

Hints¶

The timestamp for each tweet is in the attribute of 'created_at', and the format looks like this:

'Sun Jan 01 05:00:10 +0000 2017'

That’s a nice human readab le string, but how do we convert 'Jan 01' into the string '01'.

Not by doing string splitting, as we did when the CSV data had timestamps as, '2017-01-01 05:00:10'

The answer: our complex friend, the datetime object/module, with strptime and strptime methods:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/datetime.html#strftime-and-strptime-behavior

I’m going to assume you remember using the strptime() function to convert an arbitrary string into a datetime object, and strftime() to convert a datetime object into an arbitrary text string, because we used it in a previous assignment:

Example:

>>> from datetime import datetime

>>> date_text = '03/27/1905'

>>> date_obj = datetime.strptime(date_text, '%m/%d/%Y')

>>> type(date_obj)

datetime.datetime

>>> date_obj

datetime.datetime(1905, 3, 27, 0, 0)

>>> date_obj.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

'1905-03-27'

But you probably don’t want do the work of figuring out the strftime syntax for converting this messy string: 'Sun Jan 01 05:00:10 +0000 2017'

Then do what I did: Google for python convert twitter timestamp into datetime:

https://www.google.com/search?q=python+convert+twitter+timestamp+into+datetime

Which brings up this promising StackOverflow:

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/18711398/converting-twitters-date-format-to-datetime-in-python

I used one of the answers in the page to build my own helper function:

from datetime import datetime

def convert_timestamp_string(ts):

"""

ts is a timestamp string like: 'Sun Jan 01 05:00:10 +0000 2017'

returns datetime object

"""

return datetime.strptime(ts,'%a %b %d %H:%M:%S +0000 %Y')

Given a datetime object, we can use strftime to convert to a proper “YYYY-MM” string format. Proof of concept:

>>> timestr = 'Sun Jan 01 05:00:10 +0000 2017'

>>> dt = convert_timestamp_string(timestr)

>>> dt

datetime.datetime(2017, 1, 1, 5, 0, 10)

>>> dt.strftime('%Y-%m')

'2017-01'

7. Do a group count of tweets by hour, adjusted for Eastern time¶

Same concept as previous count-by-month example, except by hour.

The hour for each tweet should be adjusted for U.S. East Coast Time, and extracted as a two-character string in military format e.g. '00' and '15' instead of '12 AM' and '3 PM'.

Expected results:

[('hour', 'count'),

('00', 169),

('01', 165),

('02', 205),

('03', 190),

('04', 150),

('05', 169),

('06', 242),

('07', 251),

('08', 145),

('09', 76),

('11', 12),

('12', 7),

('14', 20),

('15', 79),

('16', 157),

('17', 182),

('18', 206),

('19', 162),

('20', 141),

('21', 159),

('22', 139),

('23', 153)]

Hints¶

Twitter provides the created_at timestamp with a “universal” reference, i.e. UTC, which, if you use Google, you’ll see is 5 hours ahead of the American East Coast.

Now, it’s a bad assumption to assume that, during the campaign, Trump only tweeted when he was back in New York or D.C. If we really cared, we could look through old news stories about campaign stops to figure out which time zone he was on a given date, and adjust accordingly...but we don’t care. We just want to create a histogram of tweets by hour, and get a rough estimate of how much late night tweeting the Donald did as a campaigner.

I’ve said before, time is a hugely complex topic when it comes to programming – I haven’t even mentioned how we should deal with Daylight Savings Time – so we’ll keep things simple. Do a straight-up addition of 5 hours to every tweet’s timestamp before extracting the hour as text.

Simplest way is to use the timedelta class that is part of datetime:

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

timestr = 'Sun Jan 01 05:00:10 +0000 2017'

# assuming you haven't wrapped the below snippet into "convert_timestamp_string"

dt = datetime.strptime(timestr, '%a %b %d %H:%M:%S +0000 %Y')

hoursadj = timedelta(hours=5)

eastern_dt = dt + hoursadj

eastern_dt.strftime('%H')

8. Count of tweets by device¶

Why is count by device interesting? Because it’s suspected that Trump likes to use his own Android phone when he wants to Tweet; and his aides control is iPhone/web twitter:

“Donald Trump seems to still be using his unsecured Android phone—and that’s troubling” https://qz.com/894753/us-president-donald-trump-seems-to-be-using-his-unsecured-android-smartphone-to-tweet-while-in-the-white-house/

Throughout his brief presidential tenure, Trump has continued to tweet from both his personal Twitter account and the official @POTUS account. As was the case before his inauguration, tweets appear split between an iPhone and an Android smartphone, which likely delineates between Trump’s aides tweeting and Trump tweeting himself. Tweets from his personal account continue to come from an Android phone, suggesting that he may be tweeting from a non-secure device.

Do a group count of tweets by device/client used to make the tweet.

Every tweet has a 'source' attribute that is HTML string like:

'<a href="http://twitter.com/download/iphone" rel="nofollow">Twitter for iPhone</a>'

We want to extract the string 'Twitter for iPhone' for each tweet, and return a sorted list of tuples of source name and count, sorted by descending order of count, and then source name alphabetically.

Expected results:

[('source', 'count'),

('Twitter for iPhone', 1560),

('Twitter for Android', 1362),

('Twitter Web Client', 276),

('Twitter for iPad', 22),

('Instagram', 2),

('Media Studio', 1),

('Periscope', 1),

('Twitter Ads', 1)]

Hints¶

Lots of examples for text extraction. You could even use BeautifulSoup/lxml to parse the source string value because it is, as far as we can tell, a HTML link in proper HTML format.

But I recommend using good ol’ regular expressions, something you may only vaguely remember from the command-line days. They are perfectly usable in Python, with eome extra overhead, including importing the re library.

Specifically, we want to use the re.search method.

https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html#re.search

It’s a bit complicated, and I invite you to play with it interactively.

Here’s a regex that uses a capturing group and then extracts the captured group as a string:

>>> import re

>>> s = 'jenny is at 555-867-5309'

>>> mx = re.search('(\d{3})-(\d{3}-\d{4})', s)

mx

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(12, 24), match='555-867-5309'>

>>> type(mx)

_sre.SRE_Match

>>> mx.group()

'555-867-5309'

>>> mx.groups()

('555', '867-5309')

Here’s a naive but seemingly functional way to extract the source “name” from the raw source:

>>> source_string = '<a href="http://twitter.com/download/iphone" rel="nofollow">Twitter for iPhone</a>'

>>> mtch = re.search('>(.+?)<', source_string)

>>> mtch.groups()

('Twitter for iPhone',)

>>> mtch.groups()[0]

'Twitter for iPhone'

9. Tweets by hour using an Android phone¶

Same as previous two exercises – extract the source information, filter tweets or Android-only, then do a group-count by hour of day.

Expected results:

[('hours', 'count'),

('00', 31),

('01', 44),

('02', 50),

('03', 53),

('04', 60),

('05', 72),

('06', 72),

('07', 79),

('08', 76),

('09', 33),

('10', 28),

('11', 4),

('12', 5),

('14', 18),

('15', 73),

('16', 151),

('17', 148),

('18', 152),

('19', 79),

('20', 45),

('21', 37),

('22', 26),

('23', 26)]

10. Number of tweets that use the word “crooked”, Android vs. iPhone¶

If it’s the case that Trump uses his Android phone when he wants to tweet something himself, then it stands to reason that tweets that come from his Android phone, according to the Twitter metadata, have statistically different composition. Here’s a nice analysis and visualization:

Text analysis of Trump’s tweets confirms he writes only the (angrier) Android half: http://varianceexplained.org/r/trump-tweets/

Every non-hyperbolic tweet is from iPhone (his staff).

— Todd Vaziri (@tvaziri) August 6, 2016

Every hyperbolic tweet is from Android (from him). pic.twitter.com/GWr6D8h5ed

Let’s hold off on the complex analysis for now. Let’s just pick a herustic and test the hypothesis. Trump was fond of calling Hillary “crooked” among other epithets - let’s count tweets by whether or not the word “crooked” was used.

Return a simple dictionary that returns the ratio of tweets that have ‘crooked’ (case-insensitive).

Expected results:

{'crooked_android_pct': 12.1, 'crooked_iphone_pct': 5.4}